Religious affiliation is changing in New Mexico as attitudes shift and politics enters the picture. In Lea County, membership in Protestant and Catholic churches alike has been declining for decades. What the data doesn’t show, however, are the personal reasons behind the changes.

Looking at the data shows how Lea County fits into the trends, and speaking with local residents about their own personal changes in religious affiliation may give some insight into why these numbers are moving in the direction they are.

By the Numbers

As a state, New Mexico ranks among the highest for the percentage of Catholics (at 34 percent). This is slightly higher than the national average, which is 25 percent.

Beyond Catholicism, Mainline and Evangelical Protestants make up the majority of the religiously affiliated at 23 and 14 percent, respectively. Altogether, 75 percent of New Mexicans identify as Christians, though this figure doesn’t reflect how many are church members.

Those who are not religious (the “nones”) represent 21 percent in New Mexico. This group includes agnostics (those who believe in God but not within the confines of religion), atheists (those who do not believe in God), and those who responded “nothing in particular”.

In Lea County, the Baptists lead the way at 22 percent, followed by Catholicism at 16.4 percent. This indicates that Lea County has approximately half the rate of practicing Catholics as the rest of the state.

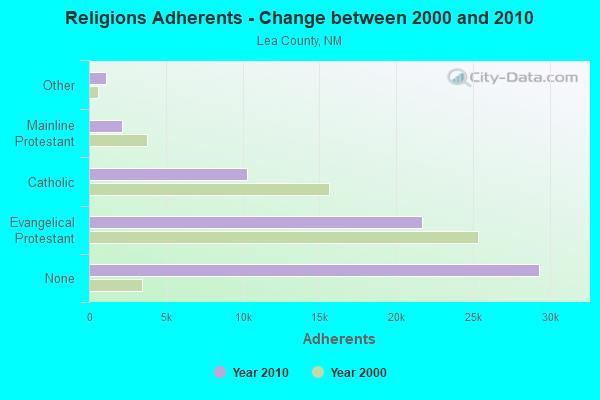

Most notably, while Protestants and Catholics have both been losing adherents since 2000, the number of “non-affiliated” in Lea County has been skyrocketing. City-data indicates that the number of non-affiliated increased from less than 5,000 in 2000 to almost 30,000 in 2010.

More recent data on the number of “nones” in Lea County isn’t readily available, but the writing is on the wall: people are leaving organized churches in significant numbers.

Perspectives in Hobbs

The reasons people are leaving churches vary from person to person. To get a firsthand perspective, we interviewed a husband (“Miguel”) and wife (“Elisa”) in Hobbs, who agreed to share their story on condition of anonymity.

For Miguel, who has lived in Hobbs for more than three decades in all, it was the presidential election cycles of 2016 and 2020 that were the deciding factor in leaving the Pentecostal church they were part of. “I got tired of seeing ‘Christians’ intentionally hurting others,” Miguel explained. “I’d seen it for a while, but maybe because I was older, I realized how damaging everything the Christian community was doing had become.”

From Miguel’s perspective, “they were losing not only unsaved souls, but also saved ones by their actions.” Rather than being loving neighbors following the instructions of Jesus, too many Christians “look with disdain upon others” and “scream hatred at others instead of showing love.”

Rather than being a place of fellowship and support, Miguel saw his church as becoming one of judgement where members were “tearing each other apart” more vigorously than non-Christians. “The Church has become a disgusting place of hatred instead of a beautiful place of love,” Miguel imparted.

Seeing what he’s seen has only reaffirmed Miguel’s desire to be a better human. “I tell others that I believe in God and the Bible, but I am a follower of Jesus, not a Christian. I do not want that negative stigma that word brings to follow me around. I want people to say they could never guess, because I’m kinder and more accepting and loving than Christians they’ve met.”

Elisa, who has similarly lived in Hobbs for more than three decades, grew up in the church environment “and loved it,” she shares. Over the past five years, however, the “ugly side” of the ministry had become too apparent to ignore as congregation members turned on one another. “We understand we’re all human and make mistakes, but these were people intentionally hurting people they had known for years, even had called family at some point.”

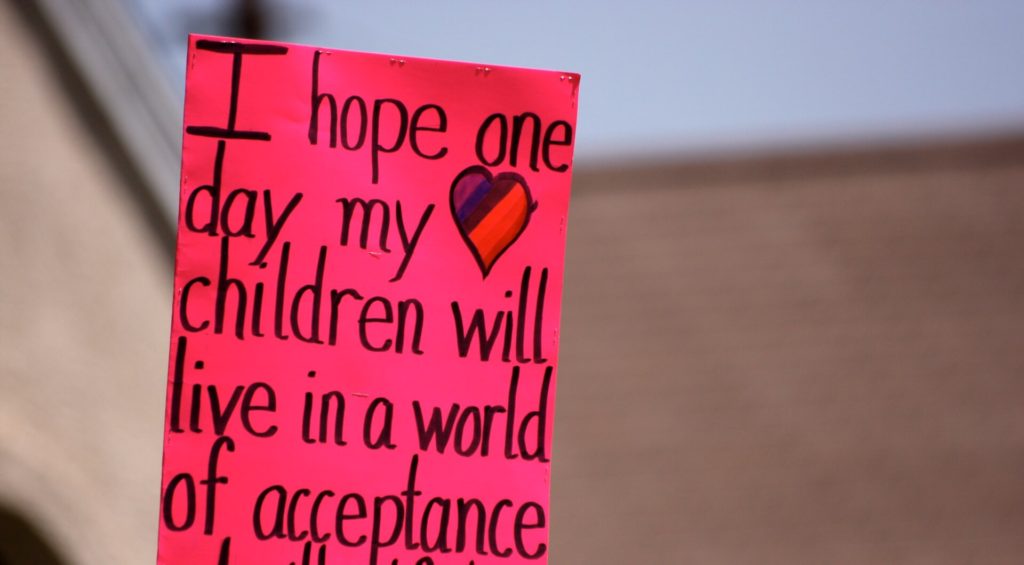

The lack of tolerance in the church became unignorable when Elisa and Miguel’s child came out to them in relation to their sexual orientation, and asked them not to tell certain people due to the amount of hate it could generate. “I have seen too many people in the church not just be okay but cheer on hate for the LGBTQ+ community,” she said.

Having a homosexual child has been “eye opening” for Elisa, she shares, and it has helped her realize how her previous approach to homosexuality was “hateful and mean” at times. “I told people I loved them but not their sin in regards to homosexuality. Now the thought of someone telling my child something like that sickens me, because I see the struggle they go through just being who they are.”

Seeing an increase in the rise of hateful behavior, Elisa says she’s not the only one that’s been noticing it. “I have heard the phrase ‘there’s no hate quite like Christian love’ so frequently these days and I don’t think that’s a coincidence.”

Outside of their need to accept and advocate for their own child, Elisa and Miguel were deeply affected by the support of former President Trump among churchgoers, she explains. “I hated seeing Christianity almost turning into a political party. It felt like everyone was following Trump, not Jesus. It was horrifying for me to see. It was like seeing the modern-day church transform into the Pharisees in real time.”

Elisa notes that the tendency among churchgoers may be to say “not my church” and to look away, but as someone who has been a part of two separate congregations, the problem is pervasive. “It’s so easy to become judgmental and rude, and you feel like it’s okay because you’re helping to save people from the fires of hell. The entire time doing the opposite of what God has actually called us to do.”

For Elisa personally, she found solace in taking Bible classes and doing a deeper dive into scripture. “I would encourage everyone to read their Bible and try to understand it,” she advises. “Somewhere along the way we’ve forgotten the Jesus who went to the woman at the well, the despised whore, the one who couldn’t even go when the other women did; the one he shouldn’t have been associated with by the standards of the times and forgave her and loved her, without berating her, without judgement.”

For Miguel and Elisa, the church no longer offered what they were looking for. Others, however, are being drawn into the church environment, and congregations for some area churches are growing as a result.

Congregations Grow with New Additions

National and global disasters tend to drive people to churches as they look for meaning and spiritual connection, and the past few years haven’t been short on them.

Even while COVID-19 necessitated the closure of indoor worship spaces, congregations and new members joined together for outdoor services and online. With indoor services now permitted again, some congregations have now grown.

Danna Mann, Ministry Assistant for the Hillcrest Baptist Church in Lovington, shares that, after declining from 110 to 75 congregation members in worship over the past decade, church membership has recovered to 100 and new members are coming each week. “A lot are long time members [who returned], but we have several new people and families,” she explains.

Along with the pandemic and other challenges drawing worshipers together, Mann attributes growth at Hillcrest to their recently-completed private Christian school, which has attracted new members.

A Mirror of National Change

What’s happening in New Mexico is, in many ways, a mirror of what’s happening nationwide. For the first time, a survey in 2020 recorded that the number of Americans who are unaffiliated with a church was higher than the number of church-goers.

The poll found that 47 percent of Americans belong to a church, down significantly from 70 percent in 1999. The number of Americans leaving particular religions or opting to study religion personally has been increasing.

For “nones” in particular, their growth has slowed slightly. From a peak of 26 percent in 2018, nones comprised 23 percent of the population in 2020.

While some churches are shrinking, others are growing on the national stage. Evangelical churches are growing faster than mainline protestant churches (42 compared to 34 percent, respectively, according to protestant pastors), while 45 percent of Baptist pastors see their churches as growing.

Social issues are deeply intertwined with church membership, meaning that as controversial policies (such as abortion) take center stage and others use religion as a platform to wage political campaigns, the division between church members and nonmembers will most likely only grow.

When political messages don’t resonate, however, the result is swift: evangelical Protestants, who were 37 percent of the Republican party in 2006, now only comprise 29 percent as the purported beliefs and actions of national figures appear to conflict with their own beliefs and virtues.

How the religious landscape will shift over the next century will ultimately depend on a number of factors. As it changes, it represents the fluctuation of vast amounts of social and political power – and the ongoing formation of a society attempting to balance between adherence to tradition and progressive adaptation in the face of new challenges.

Photo by Ethan Wright-Magoon // Unsplash